Following is an excerpt from an article by by Kamala Thiagarajan published in February 2016 issue of Forbes India Magazine

Wandering monks once made their home in South India, leaving behind an ancient legacy in the heart of the wild. Read on.

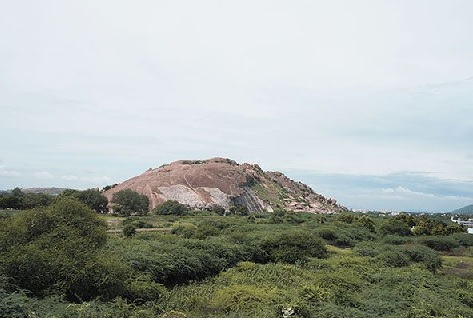

It is, without a doubt, one of the most desolate places I have visited and yet there is a wild, windswept beauty here that is at once ethereal and enchanting. Lush greenery accosts me from all sides—thick shrubs that look like huge heads of broccoli, mint green grass and swaying trees that would not be out of place in a tropical jungle. Bits of sharp gravel crunch underfoot as I walk on moss-laden stone steps forming a natural pathway that cuts through the under brush. Rising from this splendour like an omnipotent messiah is a massive wall of smooth orange rock.

The wildness of the terrain puzzles me because I’m not in a densely forested area. All this is a mere heartbeat away—15 km—from the heart of Tamil Nadu’s third largest city, Madurai, where I have lived for most of my adult life. Madurai is known for the fragrance of its jasmine flowers, the ancient grandeur of its Meenakshi Amman temple and its thriving small-scale and textile industries. For centuries now, it has had a flamboyant and interesting reputation as a cultural and religious centre of the South in which history is inseparably entwined with mythology.

And yet, though of national importance and occasionally touted in local newspapers, hidden in these hills is an incredible slice of history that has largely been overlooked. Many may have passed through this tract of land, but few would have noted that Jainism had found its way here.

How had the religion, which once flourished around the Gangetic plains of Bihar in c 750 BC, reached this part of the world? Dr Kumarpal Desai, managing trustee, Institute of Jainology in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, explains. “The Jain community was unified but then a faction broke away and travelled south in the face of a disastrous famine around c 300 BC,” he says. “Some sources suggest that a large group of migrants was led by the famous Acharya Bhadrabahu into what is now the Karnataka state (Mysore), where they resided for some twelve years.”

It is further held, he adds, that Bhadrabahu himself passed away before any return was possible, but his followers did make their way back to Pataliputra (modern Patna in Bihar) only to discover that an “official” recension of the sacred texts had been prepared in their absence. “Many points of this recension, codified under the leadership of Sthulibhadra, were unacceptable to the recently returned monks; even more significantly, the ‘northerners’ had taken up certain habits, especially the use of clothing, which the southern group found intolerable. Unable to effect any alterations either with regard to the contested doctrinal issues or to the ‘lax’ conduct of Sthulibhadra’s followers, this group (later called Digambaras) not only declared the entire canon heretical and invalid, but proclaimed themselves the only ‘true’ Jains. Eventually they wrote their own puranas (legends), giving a history of Mahavira which often contradicted the one found in the texts possessed by the other faction, the Svetambaras,” says Dr Desai.

These events marked Jainism’s remarkable journey back to the South, where the Digambaras left their mark.

“Initially, Jainism was purely an ascetic practice,” says Dr R Venkatraman, a former professor of art history, Madurai Kamaraj University. “These monks were strictly celibate and constantly nomadic. They were always fasting and believed it to be a means of controlling the wandering mind, which they considered the root cause of all sins and cycles of rebirth. Ahimsa was their ideal, but they resorted to torturing their bodies for this purpose.”

On the floor of the shallow caves on some of these hills, lined by exquisite sculptures and ancient scripts carved into stone, are deep furrows hewn into the natural boulder that I am told once served as beds for Jain monks. They are believed to have slept here during the rainy season, not so much to protect themselves from the harsh elements, but to facilitate prayer and meditation, says Venkatraman. These beds are a lasting testimony of the hard lives these saints chose to lead and of their tremendous self-control. I am determined to see them for myself.

My quest to uncover the secrets of Jain heritage in these parts begins at Samanar Malai (which translates to ‘Jain Mountain’) in the serene village of Keelakuilkudi, 11 km west of Madurai. In this seemingly innocuous agricultural village is one of the earliest known Jain monuments in Madurai. A stunning Ayyanar temple with rich colourful carvings lies beside a beautiful temple tank, riddled with moss and overflowing with lilies and lotuses. Next to the temple is a massive boulder-like mountain. Cut into its smooth, glossy surface are hundreds of shallow steps that seem to ascend to heaven. Clutching the red hot railings that line these steps on either side, I hesitate and squeeze my eyes shut. I have a chilling fear of heights, but what I rue most at this moment is my choice of fashionable open-toed sandals. Why didn’t I have the sense to come in trekking gear? But I hadn’t anticipated this sheer ascent.

After just a few steps, I am breathing heavily. Midway through this climb, the steps seem to melt away and disappear from under my feet. I am thankful for the railings and pull my way up to the vertical surface of rock, willing myself to look no further than a few feet ahead of me. Mercifully, in a matter of minutes, I reach the summit.

For all its steepness, the hillock is strangely flat at the top, rather like a flying saucer. A wall of rock lies beside a natural spring and I learn that it is called Pechipallam. Carved on this rock are stunning images of Jain tirthankaras (Jain saints who propounded the religion and embraced the cause of liberation and enlightenment). The most significant of these carvings is that of Mahavira, the last of the 24 tirthankaras. Another interesting carving is that of the ancient king Bahubali.

Bahubali, brought into mainstream pop culture by SS Rajamouli’s blockbuster movie Baahubali: The Beginning (2015), means ‘one with the strong arms’. He was the son of Rishabha, also known as Adinatha, the first tirthankara.

If you look closely at this bed of rock, you’ll see ancient Tamil-Brahmi and Kannada script scrawled on the sides. “Tamil Brahmi script is significant because this is the earliest known script in Tamil Nadu and, according to excavation reports, it dates back to pre-Ashokan times,” says Dr C Santhalingam, retired assistant director at the Tamil Nadu Department of Archaeology. He now runs the Pandya Nadu Centre for Historical Research, an NGO in Madurai. “There are 13-14 such caves in Madurai with 60-odd ancient inscriptions on the rock beds. The sculptures, however, were built much later. The Jains are believed to have preached their religion and offered medicinal services to the local people.”

Keelakuilkudi is home to another Archaeological Survey of India (ASI)-protected Jain monument called Settipodavu. This is comparatively easier to access. A five-minute walk through banyan trees will lead you to well-maintained stone steps. It’s a short climb to the top and here, with a bird’s eye view of the city behind you, you’ll find yourself face-to-face with yet another intricately carved statue of Mahavira. This statue is believed to be the largest of its kind in Tamil Nadu. Along the inner lip of the cave, you’ll find other exquisite carvings but many of these are fading away and aren’t as clear.

Stone quarrying is a constant threat, not just to the ecosystem here but to the ancient legacy of these caves. Despite ASI’s untiring effort to protect these properties as historical sites, the torn, defaced surfaces of stone suggest grave damage. Vandalism from common citizens is also a concern.

This is even more evident in other Jain caves around the city like Puliakulam and Perumalmalai.

Puliakulam is a gruelling territory to navigate. Once you manage to clamber over a vast expanse of boulders, full of spiteful thorny bushes, you’ll find a metal ladder erected by the ASI. It’s a steep climb, but once you’re up, walking along a broad ledge abutting the mountains, you’ll find ancient Tamil Brahmi script. Sadly, ignorant of its historical value, many people have carved in their own initials. There is graffiti of every kind—names, initials, hearts and arrows—much of which heartbreakingly impinges into the ancient script. I run my hands over the smooth rock, wondering how anyone is able to carve into this at all. Did pleasure seekers come equipped with chisels and pickaxes these days? Or could a mere pocket knife wreak so much havoc on what is supposed to be such a fragile piece of our past?

Near the Madurai Kamaraj University, west of Keelakuilkudi village, is Perumalmalai. Here, the landscape is similar to that of Puliakulam—dry, harsh and full of enormous sunburnt boulders. The isolation of these hills is rather forbidding. Once again, as on several occasions on this journey, I marvel at the intense need for privacy that must have driven the Jain followers to seek solace here, far from prying eyes, to lead lives of peace and sacrifice.

Not surprising when you consider how Jains were once persecuted in Madurai as far back as c 720. “As any lofty institution is susceptible to degeneration with too much contact with other humans, especially kings, Jainism too met with such a fate as they desired to convert great emperors such as the Pallavas of Kanchi and the Pandyas of Madurai,” says Dr Venkatraman. “Indeed, it is thanks to their zeal that Hinduism awoke through the Bhakti movement in Tamil Nadu around c 600-850 AD.”

Around c 820 AD, however, small, perceptible changes took place that helped the Jains make their homes here after all. A Chera princess, Queen Cheran-Ma-Devi, wife of Viranarayana, a Pandyan king who ruled these parts, was believed to have extended her patronage to the Jain monks. All the monuments seen in these caves date back to the times when Jainism flourished under her benefaction.

I pass an enormous banyan tree and, nearby, I glimpse a water bird, posing eerily with its wings outstretched, perched high on the rocky summit of a lone boulder. Leaving this poignant little creature behind, I stop abruptly when I reach an area where several boulders form natural caves. Here, I finally glimpse the sight that I had so longed to see. Etched into the floor of these caves, with more rocks jutting out overhead, are narrow rectangular furrows, all laid out side by side, each neatly and precisely carved from stone. They appeared brightly polished. These are the rock beds on which the Jain monks of yore slept.

As the sun blazed a gleaming path between the layers of orange stone, I think of how little one actually needs to survive. Perhaps that is the malaise of our times. And, perhaps, all it takes is a dramatic symbol from the past—like this ancient rocky resting place—to remind us of it.

(This article is excerpted from the latest Forbes Life India Jan-Feb 2016 issue)